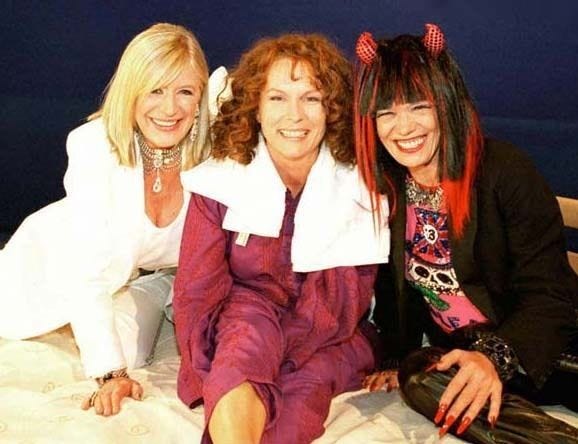

First of all, rest in peace to Marianne Faithfull, now lauded as “more than a muse” after a lifetime of being referred to as Mick Jagger’s muse. I love this Guardian story about her unexpected triumph in a 1967 production of Three Sisters, which was seen as goofy stunt casting until people actually saw her act and STFU. I also love this very poor quality video of her performing “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan” in Paris in 1979, which is a song that runs through my head more and more the older I get and this version from her 2001 appearance as God (!) on Absolutely Fabulous with Anita Pallenberg (!!) as the Devil (!!!)

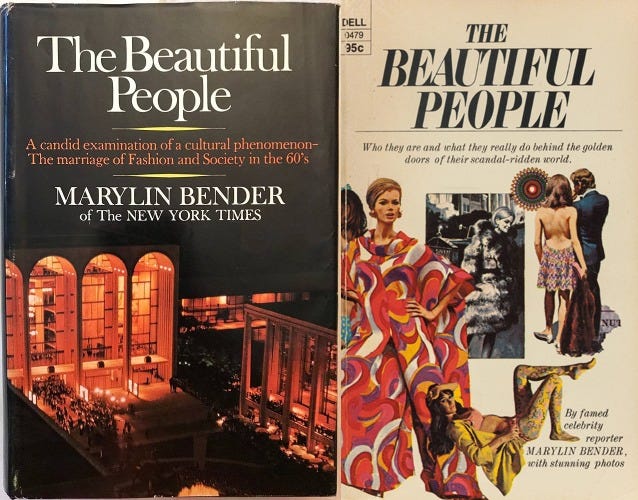

Speaking of 1967, this week’s “weird book” is The Beautiful People by Marylin Bender, then the fashion editor at The New York Times.1

Per her 2020 obit, she went on to be the paper’s Sunday Business editor in the 1970s, “one of the few women with any editing authority,” and, among other things, pissed off Donald Trump with an unflattering profile. [Pause for a good rage scream, deep breath, whatever you need, it’s fine, how are we even getting through the day, how am I even writing this, are you reading Let This Radicalize You, might I suggest some gentle somatic self-care, etc.]

1967 was a significant year, fashion-wise and otherwise. In 2017, Sheila Weller, writing for Vanity Fair, called it “the year that upended women’s fashion—and nearly everything else,” and the article is full of remembrances from the women who lived through it and includes a pretty gross yet compelling story from Warhol superstar Viva on her one-night stand with Otis Redding. It’s a good overview of the trends of the moment — the move from Mary Quant miniskirted mod looks to the Biba “rich hippie” diaphanous Ladies of the Canyon vibe, the Summer of Love, the consciousness-raising of feminism’s Second Wave, the appearance of Black models in mainstream fashion magazines. Judy Collins said:

“We were all re-writing the song, the novel, the poem of women’s lives—all of us living that year together. We said, whether to lovers or to the culture that still frowned on unruly women, “We are going to intrigue you—and gain the upper hand. Because we are iron and lace at once.”

The cover of The Beautiful People calls the book “a candid examination of a cultural phenomenon—the marriage of Fashion and Society in the 60’s.” Fashion was now a grand equalizer because “looks” (as in the way “lewks” became a concept/way of life a few years ago?) were more important than the craft, expense, snobbery, and exclusivity of haute couture that had previously kept Fashion with a capital F from the unwashed masses: “Shadow is more real than substance. Fashion is a tool in the frantic effort to prove personal or commercial merit. Advertising agencies sell airplane tickets and dentures by changing what the stewardesses or models in the television commercial wear. Social acceptance can be won with a wardrobe.” You can see why the Times tapped her to write about business to “enliven their otherwise dry pages,” according to her obituary.

She offers up the success and popularity of the Kennedys as the onset of this shift, calling JFK “an intellectual who looked like a movie star…the first authentic pop politician” and Jackie “the superconsumer of fashion,” responsible for the press becoming obsessed with asking women who they were wearing, label-wise. She also goes into the sheer volume of then-young people thanks to the Baby Boom as only someone who is 42 years old and fully aware that they have been eclipsed and left behind, pop culture-wise, can:

“In the Sixties, the fashion industry allowed itself to be tyrannized by youth…[Fashion editors and merchants] and their associates in advertising and public relations who buzzed around the mass culture honeypot were obsessed by the statistic that almost half the population is under 25 years old…Yet youngsters were contemptuous of adults who followed their lead. Sane women protested that they were being rejected by the fashion industry. For the most part, they were.”

As it ever was, so it shall be again. There’s an entire chapter about this called “From the Cradle To The Best-Dressed List and Back,” which includes this amazing paragraph:

Vogue had been recruiting juvenile goddesses ever since the beginning of the Vreeland regime in 1962. Mrs. Exeter, the protagonist of the magazine’s recurrent feature about a chic and charming grandmother, wasn’t even accorded a decent obituary. She just vanished along with elegance to be replaced by chicerinos, youthquakers, and breakaways like Cher, the feminine half of a pop singing team; Mia Farrow, the boyish-bobbed bride of Frank Sinatra; and Romina Power, the late Tyrone Power’s daughter, whom Vogue exalted at 14.

[Possible future Dames issue devoted to this mysterious Mrs. Exeter?! “Before coastal grandmother, there was Mrs. Exeter…”?!?! Stay tuned! ]

I was delighted and nervous to see that the subject of “Homosexuality” has quite a few entries in the book’s index — no gays, no fashion, no art, no ANYTHING, obviously, always, forever. In Bender’s words, “Now as always, some of the prettiest clothes are designed by homosexuals, some of the worst botches by heterosexuals.” A discussion of the concept of camp follows"2 and includes gems like “Camp came along when American fashion needed another gimmick to push the clothes that Americans didn’t really need. Homosexuals may have sponsored camp but heterosexual businessmen commercialized it.” And here we are in 2025, mourning that shittily-constructed Pride collections are being pulled from superstore racks.

Perhaps the best chapter is “The Creators,” which features, yes, designers, and includes young James Galanos (“a bachelor of medium height with the frame of an undernourished fifth-grader”), young Rudi Gernreich and his dismay over the infamy of his topless bathing (apparently it was merely a “prophecy” of what was to come as opposed to a design meant for mass consumption), and “the youngest and rashest of American’s creative designers” Betsey Johnson, who said “my clothes are for young people who are saying “Look at me — I’m alive!”” I guess they still are? [P.S. Betsey did her signature cartwheel and split at her 80th birthday party in 2022!]

The Beautiful People is available pretty widely for not very much money.

[And if you’re singing the Marilyn Manson song right now and marveling at the Marylin Bender/Marilyn Manson parallel, apparently the song was named for the book and also fuck that guy forever.]

This is just three years after the publication of Susan Sontag’s essay “Notes on “Camp””, which was and remains so effective and influential because it was an actual Queer person teaching straight culture about an inherently Queer aesthetic. There’s no way this book would exist without “Notes on “Camp”” and yet here it is in a footnote over 60 years after in publication, the symbolism, it’s punching me right in the face!

I've seldom read anything that has motivated me to read more. I'm going to head over to my local Half Price Books to see if I can find it!

Ooh great out of print book rec! I'll keep my eyes peeled for it (and my fingers crossed for a special Mrs. Exeter newsletter. What a sophisticated/ preppy perfect name.)